About

About the Database

Daydreams («Грезы») is the first scholarly database of feature films produced in the Russian Empire; it also includes films produced in its former territories during the first years after the October Revolution. It contains the most complete filmographies, synopses, and iconographic materials (such as promotional stills, posters, frame enlargements) for more than 2,500 films produced in 1907—1919.

The title of the database comes from the canonical film by Evgenii Bauer, Daydreams (Грезы; 1915), an adaptation of Georges Rodenbach’s novel The Dead Bruges. At the time, the concept of daydreams was among the most important in various reflections on and discussions of early Russian film; in this context,Maxim Gorky was the first to use the word “daydreams” in his groundbreaking essay about cinema written in 1896. Daydreams, Light Daydreams, Magical Daydreams — dozens of motion picture theaters all over the country had such names.

This project was launched in January 2022 when Anna Kovalova started teaching an online course, “Cinema of the Russian Empire: History, Poetics, and Iconography,” at Brīvā Universitāte / Free University. A group of students under her supervision began building up the database content, and this work has been supported by many scholars and volunteers since then. Data engineer Alexander Grebenkov has been developing the database and the website.

Database Structure

The database is divided into sections chronologically, each section representing a year. Within the year, films are arranged alphabetically. It is also possible to arrange the films in alphabetical order. Each film has its own web page, where a filmography is followed by information on the film’s survival status and the location of its script, if one exists. When it is possible to locate a film libretto—an original film synopsis—its full text is published after the filmography. In case several librettos are known to exist, all are published in their entirety. Illustrations such as production stills, posters, and frame enlargements are added to the page.

The database is bilingual, Russian and English. Many sources, such as film posters and photos, do not require a translation, but all the filmographic and bibliographical references for each film are being translated into English. Currently, we have prepared brief English filmographic notes for films produced in 1917 and 1918; these translations do not include alternative titles, references, and synopses. For this information, please consult the Russian version of the database and use automatic translation tools when needed; proper English translations for all the materials will be added over time.

Filmography

Filmographic notes were prepared by film scholar Aleksandr Deriabin based on all available filmographies and catalogs relevant to the period:

- Deriabin, Alexander, and Valerii Fomin, eds. Letopis’ rossiiskogo kino 1863–1929. Moscow: Materik, 2004.

- Ivanova, Vera, Myl’nikova, Viktoriia, Skovorodnikova, Svetlana, Tsivian, Yuri, and Yangirov, Rashit. Velikii kinemo: Katalog sokhranivshikhsia igrovykh fil´mov Rossii 1908–1919. Moscow: NLO, 2002.

- Kino-biulleten’ Kino-komiteta Narodnogo komissariata prosveshcheniia: ukazatel’ kartin, prosmotrennykh otdelom retsenzii Kinematograficheskogo komiteta Narodnogo komissariata prosvesh’eniia, vyp. 1 and 2. Moscow, 1918.

- Mislavskii, Vladimir. Faktograficheskaia istoriia kino v Ukraine, vols. 1 and 2. Kharkiv: Toring-plus, 2013.

- Semerchuk, Vladimir. V starinnom rossiiskon illiuzione . . . annotirovannyi katalog sokharanivshikhsia igrovykh i animatsionnykh fil’mov Rossii (1908–1919). Moscow: Gosfilmofond Rossii, 2013.

- Sovetskie khudozhesvennye fil’my. Annotirovannyi katalog, vol. 1. Iskusstvo, 1961.

- Vishnevskii, Veniamin. “Katalog fil’mov chastnogo proizvodstva.” Sovetskie khudozhesvennye fil’my. Annotirovannyi katalog, vol. 3. Iskusstvo, 1961, 248–305.

- Vishnevskii, Veniamin. Khudozhestvennyie fil’my dorevoliutsionnoi Rossii. Moscow: Goskinoizdat, 1945.

Film historian Peter Bagrov is currently working on a new filmography, largely based on primary sources from the 1900s-1910s. Other scholars (such as Anna Kovalova, Viktoriia Safronova, and Irina Zubatenko) keep discovering new information. Scholarly editing of filmographic sources is an ongoing task that cannot be completed within certain time limits. Filmographic notes will be updated regularly, and all the database users willing to provide relevant information are welcome to take part in this process.

Librettos

Synopses, or librettos, as they were known in Russia — short descriptions of film plots — were an important part of the film industry. In the first decades of narrative filmmaking in Russia, the trade press published librettos regularly; they were also reproduced in handbills that viewers could get at the motion picture theaters. The first attempt to collect film librettos in a scholarly database was made by Anna Kovalova and a group of undergraduate and graduate students of the Higher School of Economics University, Moscow. At the beginning of 2018, they launched a research team project, Early Russian Film Prose. The principal aim of this group was to gather the most complete collection of Russian film librettos from 1908 to 1917. This database is now available online; currently it contains 886 librettos .

However, in many ways, this database was imperfect. The new project should use a different corpus of librettos. First of all, the old database contained librettos of films produced before 1918; the new one also includes librettos from 1918 to 1919, with the section of 1917 significantly expanded. Secondly, since the first database was launched, many new librettos from 1907 to 1916 have been found. For instance, in the old database, there is no libretto for Anna Karenina (1914, directed by Vladimir Gardin), an adaptation of Tolstoy’s novel, which was very popular at the time and remains a canonical prerevolutionary film. The new database provides two librettos for the film. It became possible to add many new librettos due to expansion of sources that the current database is based on (on this, see below). Thirdly, the 2018 database was constructed according to a hierarchy of periodicals that does not appear relevant anymore. Following that system, if the database compilers had different versions of the same libretto, they always chose the one published in Sine-Fono. This journal was indeed the main film periodical in the Russian Empire, and that is exactly why it did not have enough space to publish the most complete versions of librettos. As one can see now, the Sine-Fono librettos are often shortened and usually lack titles of individual film parts that could be found in other sources. From this perspective, Sine-Fono should be the last source to take a libretto from; in most cases, it seems reasonable to check other sources when possible. One should consider each case individually, compare all versions, and choose the one which is the most complete. For instance, the periodical Sinema-Pate, published by Pathé Frêres, usually provides the most detailed librettos for films produced by that company.

Currently, the new database provides librettos of films produced in 1917 and 1918. The remaining corpus will be added over time.

Illustrations

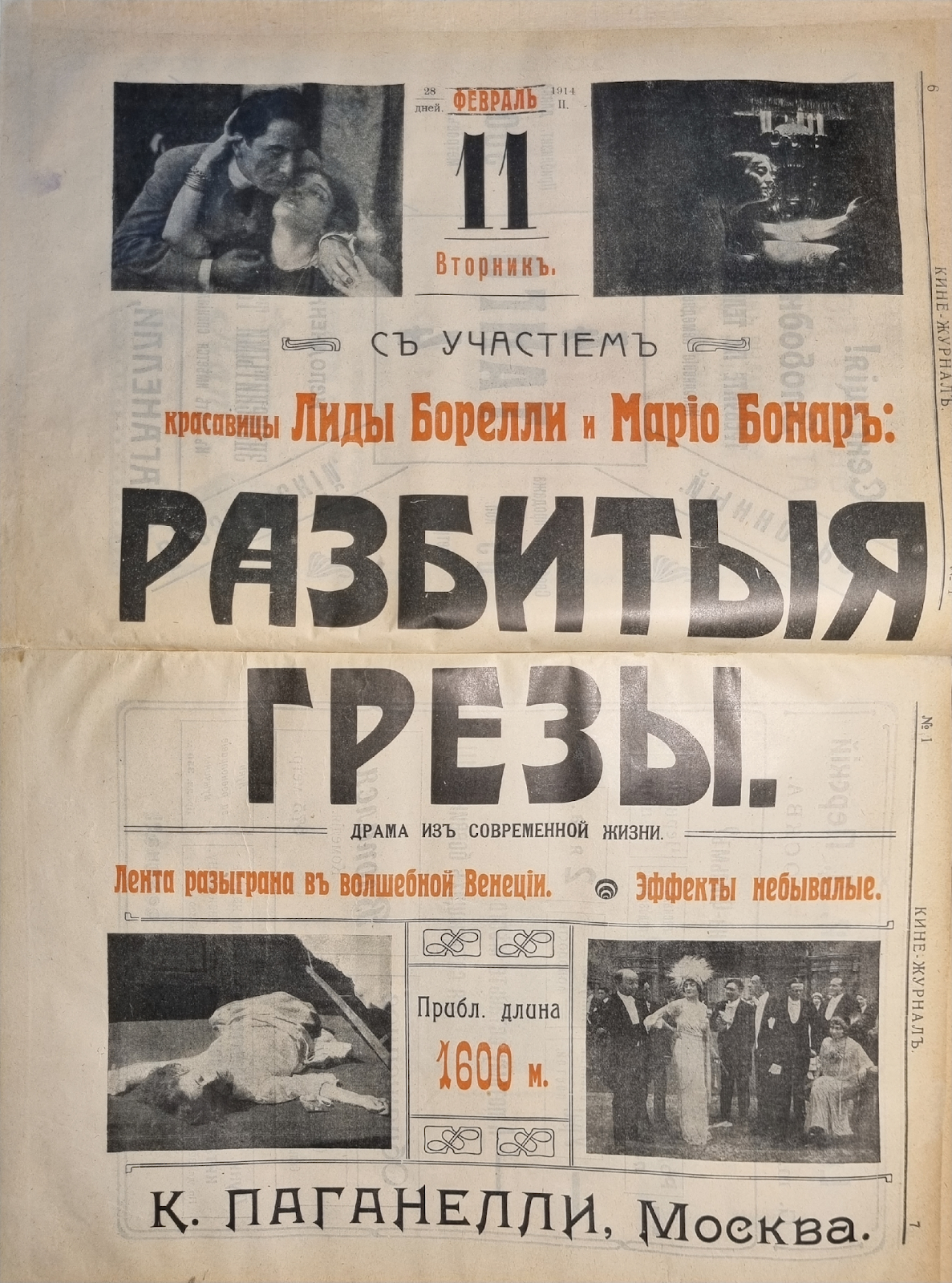

Iconographic materials presented in the database are of many different kinds, yet most of them can be classified into three main groups: frame enlargements, promotional stills, film posters, and postcards.

Frame enlargements were made directly from the film. In some cases, they were taken from the surviving prints and negatives. Of special interest are frame clippings taken from the original nitrate prints from 1900s-1910s. They capture not only the original composition and lighting but the authentic colours as well (be that tinting, toning, stencil colouring, etc.). The latter is of particular value, since most of the films produced in the Russian Empire have survived in later black-and-white copies.

Promotional stills were the basic tool for film producers and distributors to advertise a film. They were published widely in film and theater periodicals and in handbills, of which very few have survived. For scholars, promotional stills turn out to be the main source for reconstructing the visual style of a film that has been lost. They give an idea of the setting and costumes; often they are helpful for identifying actors. However, one should not rely on promotional stills too much; these photographs were rarely printed from the film itself – they are not frame enlargements. Usually, a studio photographer took them specifically for advertising purposes. That is why the lighting and setup are different from what one could see in the actual film.

Posters for films produced in the Russian Empire have been preserved in many museums and libraries; some of them are published in annotated albums and coffee-table books. Many of these posters reproduce promotional stills that could not be found in the trade press. Other posters do not feature any photographs, only graphic images. These can also provide useful information on specific films or cinema of the period in general.

In the Russian Empire, most film-related postcards were portraits of the biggest stars: Ivan Mozzhukhin, Vera Kholodnaya, Vitol’d Polonskii, Zoia Barantsevich, and others. There were also postcards reproducing scenes from specific films. Many of these images duplicate promotional stills, but it is important to use them in the database whenever possible since postcards are usually of better quality than stills from periodicals.

Sources

The principal sources for collecting synopses and iconographic materials are film and theatre periodicals of 1907 to 1919, which include:

- Ekran Rossii (Russia’s Screen), Moscow, 1916–1917

- Illiustrirovannaia kino-nedelia (Illustrated Film Week), Moscow, 1918

- Iuzhanin (The Southener), Rostov-on-Don, 1915–1916

- Kinematograf (The Cinematograph), Rostov-on-Don, 1915

- Kinematograf (The Cinematograph), St. Petersburg, 1915–1916

- Kinematograficheskii teatr (The Cinematograph Theatre), St. Petersburg, 1910–1911

- Kinemo, Moscow, 1909–1910

- Kine-zhurnal (Cine-Journal), Moscow, 1910–1917

- Kino (Cinema), Riga, 1916

- Kino-gazeta (Cinema Newspaper), Moscow, 1918

- Kino-kurier (Cine-Courier), St. Petersburg, 1913–1914

- Kino-teatr (Motion Picture Theater), Moscow, 1918–1919

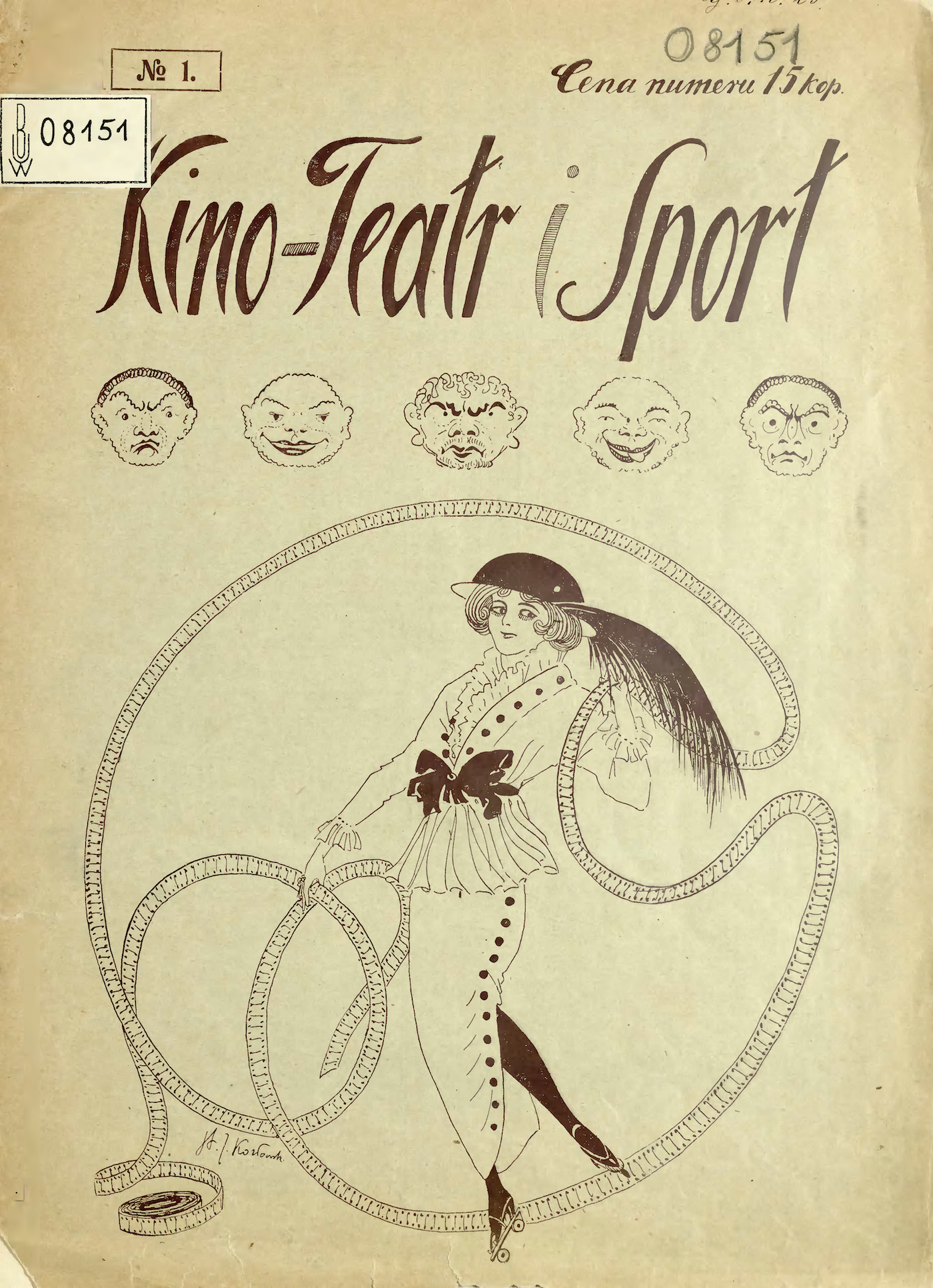

- Kino-teatr i sport (Cinema, Theater, and Sport), Warsaw, 1914

- Kurier sinematografii (The Cinematography Courier), Revel (now Tallinn), 1913

- Mel’pomena (Melpomene), Odessa, 1918–1919

- Mir ekrana (Screen World), Moscow, 1918

- Nemoe iskusstvo (Silent Art), Moscow, 1918

- Pegas (Pegasus), Moscow, 1915–1917

- Proektor (Projector), Moscow, 1915–1918

- Sine-Fono (Cine-Phono), Moscow, 1907–1918

- Sinema (also known as Kinema) [Cinema], Rostov on Don, 1913–1916

- Sinema-Pate (Cinema- Pathé), Moscow, 1910–1914

- Teatral’naia gazeta (Theatre Newspaper), Moscow, 1913–1918

- Vestnik kinematografii (The Herald of Cinematography), Moscow, 1911–1917

- Vestnik zhivoi fotografii (The Herald of Living Photography), St. Petersburg, 1909

- Zhivoi ekran (The Living Screen), Rostov-on-Don, 1912–1917

Handbills preserved at museums, libraries, archives, as well as at private collections have also become an important source for the database. The editorial team is deeply grateful to individuals who have shared their unique collections.

Copyright Note

You are welcome to use the Daydreams materials for educational and scholarly purposes as long as you credit the database appropriately. When using images and quoting texts, please credit Daydreams in the following (or an equivalent) style: Daydreams Database: Cinema of the Russian Empire and Beyond [edited by Anna Kovalova, developed by Alexander Grebenkov] https://daydreams.museum/.

About the Database

Daydreams («Грезы») is the first scholarly database of feature films produced in the Russian Empire; it also includes films produced in its former territories during the first years after the October Revolution. It contains the most complete filmographies, synopses, and iconographic materials (such as promotional stills, posters, frame enlargements) for more than 2,500 films produced in 1907—1919.

The title of the database comes from the canonical film by Evgenii Bauer, Daydreams (Грезы; 1915), an adaptation of Georges Rodenbach’s novel The Dead Bruges. At the time, the concept of daydreams was among the most important in various reflections on and discussions of early Russian film; in this context,Maxim Gorky was the first to use the word “daydreams” in his groundbreaking essay about cinema written in 1896. Daydreams, Light Daydreams, Magical Daydreams — dozens of motion picture theaters all over the country had such names.

This project was launched in January 2022 when Anna Kovalova started teaching an online course, “Cinema of the Russian Empire: History, Poetics, and Iconography,” at Brīvā Universitāte / Free University. A group of students under her supervision began building up the database content, and this work has been supported by many scholars and volunteers since then. Data engineer Alexander Grebenkov has been developing the database and the website.

Database Structure

The database is divided into sections chronologically, each section representing a year. Within the year, films are arranged alphabetically. It is also possible to arrange the films in alphabetical order. Each film has its own web page, where a filmography is followed by information on the film’s survival status and the location of its script, if one exists. When it is possible to locate a film libretto—an original film synopsis—its full text is published after the filmography. In case several librettos are known to exist, all are published in their entirety. Illustrations such as production stills, posters, and frame enlargements are added to the page.

The database is bilingual, Russian and English. Many sources, such as film posters and photos, do not require a translation, but all the filmographic and bibliographical references for each film are being translated into English. Currently, we have prepared brief English filmographic notes for films produced in 1917 and 1918; these translations do not include alternative titles, references, and synopses. For this information, please consult the Russian version of the database and use automatic translation tools when needed; proper English translations for all the materials will be added over time.

Filmography

Filmographic notes were prepared by film scholar Aleksandr Deriabin based on all available filmographies and catalogs relevant to the period:

- Deriabin, Alexander, and Valerii Fomin, eds. Letopis’ rossiiskogo kino 1863–1929. Moscow: Materik, 2004.

- Ivanova, Vera, Myl’nikova, Viktoriia, Skovorodnikova, Svetlana, Tsivian, Yuri, and Yangirov, Rashit. Velikii kinemo: Katalog sokhranivshikhsia igrovykh fil´mov Rossii 1908–1919. Moscow: NLO, 2002.

- Kino-biulleten’ Kino-komiteta Narodnogo komissariata prosveshcheniia: ukazatel’ kartin, prosmotrennykh otdelom retsenzii Kinematograficheskogo komiteta Narodnogo komissariata prosvesh’eniia, vyp. 1 and 2. Moscow, 1918.

- Mislavskii, Vladimir. Faktograficheskaia istoriia kino v Ukraine, vols. 1 and 2. Kharkiv: Toring-plus, 2013.

- Semerchuk, Vladimir. V starinnom rossiiskon illiuzione . . . annotirovannyi katalog sokharanivshikhsia igrovykh i animatsionnykh fil’mov Rossii (1908–1919). Moscow: Gosfilmofond Rossii, 2013.

- Sovetskie khudozhesvennye fil’my. Annotirovannyi katalog, vol. 1. Iskusstvo, 1961.

- Vishnevskii, Veniamin. “Katalog fil’mov chastnogo proizvodstva.” Sovetskie khudozhesvennye fil’my. Annotirovannyi katalog, vol. 3. Iskusstvo, 1961, 248–305.

- Vishnevskii, Veniamin. Khudozhestvennyie fil’my dorevoliutsionnoi Rossii. Moscow: Goskinoizdat, 1945.

Film historian Peter Bagrov is currently working on a new filmography, largely based on primary sources from the 1900s-1910s. Other scholars (such as Anna Kovalova, Viktoriia Safronova, and Irina Zubatenko) keep discovering new information. Scholarly editing of filmographic sources is an ongoing task that cannot be completed within certain time limits. Filmographic notes will be updated regularly, and all the database users willing to provide relevant information are welcome to take part in this process.

Librettos

Synopses, or librettos, as they were known in Russia — short descriptions of film plots — were an important part of the film industry. In the first decades of narrative filmmaking in Russia, the trade press published librettos regularly; they were also reproduced in handbills that viewers could get at the motion picture theaters. The first attempt to collect film librettos in a scholarly database was made by Anna Kovalova and a group of undergraduate and graduate students of the Higher School of Economics University, Moscow. At the beginning of 2018, they launched a research team project, Early Russian Film Prose. The principal aim of this group was to gather the most complete collection of Russian film librettos from 1908 to 1917. This database is now available online; currently it contains 886 librettos .

However, in many ways, this database was imperfect. The new project should use a different corpus of librettos. First of all, the old database contained librettos of films produced before 1918; the new one also includes librettos from 1918 to 1919, with the section of 1917 significantly expanded. Secondly, since the first database was launched, many new librettos from 1907 to 1916 have been found. For instance, in the old database, there is no libretto for Anna Karenina (1914, directed by Vladimir Gardin), an adaptation of Tolstoy’s novel, which was very popular at the time and remains a canonical prerevolutionary film. The new database provides two librettos for the film. It became possible to add many new librettos due to expansion of sources that the current database is based on (on this, see below). Thirdly, the 2018 database was constructed according to a hierarchy of periodicals that does not appear relevant anymore. Following that system, if the database compilers had different versions of the same libretto, they always chose the one published in Sine-Fono. This journal was indeed the main film periodical in the Russian Empire, and that is exactly why it did not have enough space to publish the most complete versions of librettos. As one can see now, the Sine-Fono librettos are often shortened and usually lack titles of individual film parts that could be found in other sources. From this perspective, Sine-Fono should be the last source to take a libretto from; in most cases, it seems reasonable to check other sources when possible. One should consider each case individually, compare all versions, and choose the one which is the most complete. For instance, the periodical Sinema-Pate, published by Pathé Frêres, usually provides the most detailed librettos for films produced by that company.

Currently, the new database provides librettos of films produced in 1917 and 1918. The remaining corpus will be added over time.

Illustrations

Iconographic materials presented in the database are of many different kinds, yet most of them can be classified into three main groups: frame enlargements, promotional stills, film posters, and postcards.

Frame enlargements were made directly from the film. In some cases, they were taken from the surviving prints and negatives. Of special interest are frame clippings taken from the original nitrate prints from 1900s-1910s. They capture not only the original composition and lighting but the authentic colours as well (be that tinting, toning, stencil colouring, etc.). The latter is of particular value, since most of the films produced in the Russian Empire have survived in later black-and-white copies.

Promotional stills were the basic tool for film producers and distributors to advertise a film. They were published widely in film and theater periodicals and in handbills, of which very few have survived. For scholars, promotional stills turn out to be the main source for reconstructing the visual style of a film that has been lost. They give an idea of the setting and costumes; often they are helpful for identifying actors. However, one should not rely on promotional stills too much; these photographs were rarely printed from the film itself – they are not frame enlargements. Usually, a studio photographer took them specifically for advertising purposes. That is why the lighting and setup are different from what one could see in the actual film.

Posters for films produced in the Russian Empire have been preserved in many museums and libraries; some of them are published in annotated albums and coffee-table books. Many of these posters reproduce promotional stills that could not be found in the trade press. Other posters do not feature any photographs, only graphic images. These can also provide useful information on specific films or cinema of the period in general.

In the Russian Empire, most film-related postcards were portraits of the biggest stars: Ivan Mozzhukhin, Vera Kholodnaya, Vitol’d Polonskii, Zoia Barantsevich, and others. There were also postcards reproducing scenes from specific films. Many of these images duplicate promotional stills, but it is important to use them in the database whenever possible since postcards are usually of better quality than stills from periodicals.

Sources

The principal sources for collecting synopses and iconographic materials are film and theatre periodicals of 1907 to 1919, which include:

- Ekran Rossii (Russia’s Screen), Moscow, 1916–1917

- Illiustrirovannaia kino-nedelia (Illustrated Film Week), Moscow, 1918

- Iuzhanin (The Southener), Rostov-on-Don, 1915–1916

- Kinematograf (The Cinematograph), Rostov-on-Don, 1915

- Kinematograf (The Cinematograph), St. Petersburg, 1915–1916

- Kinematograficheskii teatr (The Cinematograph Theatre), St. Petersburg, 1910–1911

- Kinemo, Moscow, 1909–1910

- Kine-zhurnal (Cine-Journal), Moscow, 1910–1917

- Kino (Cinema), Riga, 1916

- Kino-gazeta (Cinema Newspaper), Moscow, 1918

- Kino-kurier (Cine-Courier), St. Petersburg, 1913–1914

- Kino-teatr (Motion Picture Theater), Moscow, 1918–1919

- Kino-teatr i sport (Cinema, Theater, and Sport), Warsaw, 1914

- Kurier sinematografii (The Cinematography Courier), Revel (now Tallinn), 1913

- Mel’pomena (Melpomene), Odessa, 1918–1919

- Mir ekrana (Screen World), Moscow, 1918

- Nemoe iskusstvo (Silent Art), Moscow, 1918

- Pegas (Pegasus), Moscow, 1915–1917

- Proektor (Projector), Moscow, 1915–1918

- Sine-Fono (Cine-Phono), Moscow, 1907–1918

- Sinema (also known as Kinema) [Cinema], Rostov on Don, 1913–1916

- Sinema-Pate (Cinema- Pathé), Moscow, 1910–1914

- Teatral’naia gazeta (Theatre Newspaper), Moscow, 1913–1918

- Vestnik kinematografii (The Herald of Cinematography), Moscow, 1911–1917

- Vestnik zhivoi fotografii (The Herald of Living Photography), St. Petersburg, 1909

- Zhivoi ekran (The Living Screen), Rostov-on-Don, 1912–1917

Handbills preserved at museums, libraries, archives, as well as at private collections have also become an important source for the database. The editorial team is deeply grateful to individuals who have shared their unique collections.

Copyright Note

You are welcome to use the Daydreams materials for educational and scholarly purposes as long as you credit the database appropriately. When using images and quoting texts, please credit Daydreams in the following (or an equivalent) style: Daydreams Database: Cinema of the Russian Empire and Beyond [edited by Anna Kovalova, developed by Alexander Grebenkov] https://daydreams.museum/.

I. M. Pacatus, “Beglye zametki,” Nizhegorodskii listok (Nizhnii Novgorod), July 4, 1896, 3; A. P-v, “S vserossiiskoi vystavki (ot nashego korrespondenta). Sinematograf Lumiera,” Odesskie Novosti, July 6, 1896, 2. See the English translation by Leda Swan of one of Gorky’s texts reproduced in Jay Leyda’s Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film (George Allen & Unwin, 1960), 407–9.

Librettos of Russian Films 1908–1917. This database was created by members of the research team: Anna Andreeva, Alexander Anisimov, Anna Gudkova, Yulia Kozitskaya, Arina Ranneva, Sabina Shmakova, Nadezhda Shmulevich, Alexandra Zakharova, Julian Graffy, and Anna Kovalova.

Nina Baburina, ed., Plakat nemogo kino. Rossiia, 1900–1930 (Moscow: Art-rodnik, 2001); Maria Terekhova, ed., Plakat nemogo kino v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo muzeia istorii Sankt-Peterburgs, 1914–1919 (St. Petersburg: GMI SPb, 2018); E. V. Barkhatova, M. U. Mel’nikova, and A. F. Esono, eds., Rannii russkii kinoplakat 1908–1919 gg. iz sobraniia Rossiiskoi natsional’noi biblioteki (St. Petersburg: RNB, 2019).